Who are we when no one is looking, and who are we when everyone is? When no one is looking do we still prepare, choose, strategise for the gazes we know are coming? The judgements? The silent expectations that the eyes convey? The casual “this says a lot about you”?

Instead of photographing many people, I follow one character through ordinary spaces: hostel room, park, campus corners, staircase. Onto these familiar scenes I have introduced objects that denote the different things we put on and take off every day mentally. Fish, eyes, crowns, childhood fragments, cultural headgear, bottles and props appear and disappear around me. None of them are realistic in the usual sense, but all of them point to things we put on and take off in our heads every day.

The central question is simple: how much of “me” is actually mine? Are the masks real? Are they different versions of myself? What am I without them? Which masks feel borrowed? What do I do with the borrowings when I have to give them back?

But to whom? Visually, the narrative moves from external pressure to internal negotiation. At first, the threat is outside: a swarm of staring fish, repeated eyes, grids closing in. Later, the forces come closer to the body: hands grabbing, masks hovering, a crown drawn onto my head, a ball placed between my legs, a bottle in my hand. By the end, the scenes quiet down. I face a mask across my bed or stand in a room holding the weight of a scarf and cap, almost like a uniform. The question shifts from “Who is watching me?” to “What am I doing to myself to be watchable?”

The scope of the project is deliberately small and personal. I am not trying to represent “all women” or “all young people”. I am just sitting with one person’s confusion about identity and performance and seeing how far that can go visually. By placing unreal elements inside real locations, the essay also questions the idea of the photograph as “evidence”. If I can change my face or surround myself with impossible objects, does the picture become a lie, or does it finally show something that plain reality hides too well?

The objective is not to arrive at a final, clear self. Instead, it is to build a chain of moments that keeps the viewer asking: Which version here feels honest? Which one feels fake but familiar? Where does the character look like she has chosen her mask, and where does the mask look like it has chosen her? The essay invites the viewer to move through these scenes as if they are walking through someone’s mind and to notice, quietly, the masks they recognise from their own life.

Swallowed.

The fish sit where the background should be and turn into a kind of living wallpaper of eyes. Each fish has two big eyes that seem to look in different directions at once, and for me they stand in for other people’s gaze and their expectations – always there, not always invited, rarely in agreement with each other. Even the fish are confused: are they looking left, right, at me, or past me? So which way am is she supposed to look to meet them halfway?

She stands in the middle of all this, wedged between the trees, staring straight into the camera with a flat expression. No mask yet, no performance, just a face that has run out of reactions. This image sets up the central idea of the essay: before we even choose who, we want to be, we are already surrounded by opinions about who we should be.

Meditations

In this image the subject is no longer surrounded by gazes; she is sitting inside one. The eye becomes a kind of chamber, lined with lashes and backed by a fading forest. Is being held in someone’s gaze, or even in one’s own a form of safety, or another way of being trapped? The trees behind the iris look worn and brittle, like old beliefs and judgements that the gaze still carries as unquestioned truth. She sits cross-legged with her eyes closed, holding a bottle carefully in her lap. The bottle stands in for coping – the private rituals and substances people turn to when the outside world becomes too sharp. The gaze is no longer only something that comes from outside. It has become a space she occupies, and a way she has started to watch and manage herself.

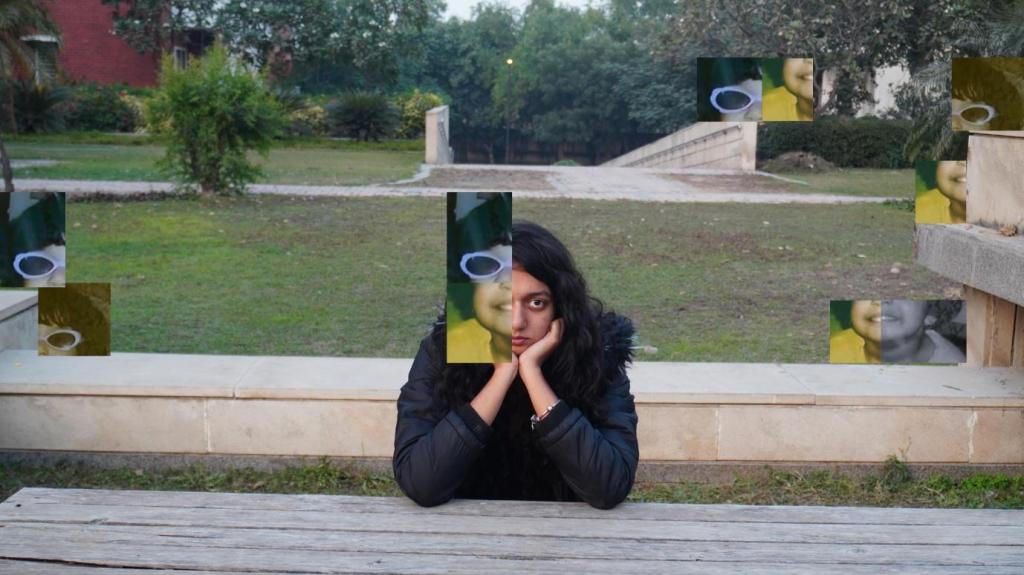

Was it all that simple before?

Here the park is quiet and open, but the frame is crowded in a different way. Small squares of an old photograph drift across the scene: a wide smile, a yellow shirt, a purple sunglass. One of those fragments sits directly over half the subject’s face, so that the child and the present-day version share the same head for a moment. Were the fragments of my earlier self any truer? The times I didn’t realise I was wearing a mask? The times I smiled from jaw to jaw knowing no trouble? The time I wore a purple sunglass and a bright yellow top? The scattered tiles behave like memories that keep popping up uninvited, insisting that there was once a simpler, truer person to go back to. The past becomes another mask to negotiate – one more face that does not fully match the one she is wearing now.

Puppeteer.

In this frame the subject walks up a stairwell wearing a rabbit mask, while a thin column of disembodied hands climbs her. The human face has been fully replaced with only the mask looking out. The hands don’t belong to any visible person, which makes them feel like instructions or habits that have been absorbed so deeply they no longer need a speaker. The scene is not about someone literally shouting orders from outside. What thoughts, judgments and rules are moving this body that did not begin with her? Family, culture, gender, social media – once their voices have been repeated enough, they start to act like invisible strings. What do I hold in my mind that isn’t my own?

Becomings of a Watcher.

The subject is perched on a cart with a travel bag at her side, as if between places, not quite arriving or leaving. Around her, flat panels with a single eye hang in the air. They cut across the pillars and background and stand in for all the outside watching that has followed her through the earlier images. The centre panel is placed so that it drops exactly between her hands, which are resting on her knee and form a loose V around it. The eye is no longer just out there; it is now sitting in the space she holds in front of herself. The external gaze and her own body literally meet in the middle. She combines her gaze with the eye’s. Is the only way to escape to become a watcher? The question underneath the picture is simple: when someone is watched long enough, do they start carrying the watcher inside them? In the flow of the essay, this image shows the point where the boundary between “they are looking at me” and “I am looking at myself the way they do” starts to disappear.

The ghosts in my bed.

Back in the hostel room, everything is familiar: the lamp, the cluttered shelf, the unmade bed. The only strange thing is what’s lying on the pillow opposite the girl – two masks facing her. One is cracked and heavy, the other long-beaked and sharp. She isn’t wearing either; she just lies there, chin in hand, staring at them. They’ve been put down, almost politely, so she can look at them properly. Which one fits the next situation? Which one will match the direction of all those earlier gazes – the fish eyes that never agreed on where she should look? Left, or right? Where are the eyes of the fishes pointing to? The quiet habit of planning how to appear before stepping out of a room. It suggests that after enough outside control, some of the work of managing identity is simply done alone, on the bed, in negotiation with the masks we keep ready at arm’s length.

The heavy uniform.

She stands bent slightly forward, looking straight into the camera, wearing a traditional cap and a long scarf. Above her head, on the loft, are stacked suitcases and boxes. Together they form a visual of all the baggage being literally on top of her. She’s alone but she carries the baggage on the head. The cap is the main “mask” here. It signals a cultural identity that is often worn with pride but can also feel like weight – a reminder to behave a certain way, represent a community correctly, live up to stories attached to that cloth. The scarf draped down her shoulders turns that identity into a kind of uniform. The expression on her face keeps the question open – is this a comfortable fit, or just another version she has learnt to balance on her head?

The gods – angered.

The subject sits on the floor, cap and scarf still on, legs stretched out, a basketball resting between them. On the cupboard door above her hangs a bright ritual mask – a kind of god-face borrowed from performance and worship. It hovers over her like a supervisor. The stakes feel different. The guilt of being watched. The cap and scarf say she is doing her part, carrying the identity she has been handed. The mask on the door becomes the god of culture, checking quietly whether she is keeping to the path laid out by ancestors. “Don’t anger the gods” or “This isn’t our culture” is often just another way of saying “don’t step out of line”. The ball, sitting right at the centre of her body, stands for her own wants and interests. To pick up the ball and move freely, does she first have to take off the cap – or can she hold both without apology?

Buzzfeed quizzes turned into psychology.

How you pour a drink says a lot about you. What you drink says a lot about you. Which mug you pour it in says a lot about you. So much everyday behaviour is read like a personality test. “Says a lot about you” – is it a small accusation or a reminder that someone is taking notes? Above her head a cartoon crown is drawn in the same colour as the liquid, as if whatever she is drinking immediately becomes part of her image.

The subject’s expression cuts against that. She is not celebrating; she just wanted that drink in that instant. The picture asks what happens to identity if every small choice is treated as permanent proof of character. If she drinks something else tomorrow, does that cancel the crown or simply replace it with another one? The fear of being fixed, constant and predictable hangs over her like a reward she never really asked for.

The gridlines.

The ropes make a neat pattern between the subject and the camera, like a ready-made graph or checklist: straight lines, fixed boxes. She sits behind it with both hands on the sides, arms locked, looking straight through the gaps. At first the grid reads like a cage, another structure closing in after all the eyes, gods and labels. But the grip of her hands complicates that. Is she trapped behind it, or is she the one keeping it in place? Is she about to pull it closer, because these lines also give her something solid to hold on to, or is she one push away from sending it swinging out of the frame? This image ends the essay on that uncertainty. The systems that shape her – family, culture, memory, performance, have not disappeared, they are still right in front of her. The difference now is that they are visible and literally in her hands. The photograph leaves open whether she steps back into the boxes or chooses to move them and asks if that small space between holding and pushing is where a less scripted self might start.