Achievement over Ascription—the Plight of Modern Education

On his return from Kashi to their village in Bengal, after his father passed away, Apu gets gravitated towards school, almost magically—like an iron-pin jumps on to a magnet. It is a very strong pull. One day, while returning after finishing his priestly obligations that are being imposed on him, he peeps into the village school. It is a love-at-the-first-sight. He is convinced. As if he belonged to that space called the ‘school’.

Apu gets an instant urge to study in the village-school. He conveys that hesitantly, yet assertively, to his mother—Sarbajaya. When she tries to discourage him by sighting the poverty as an excuse—very innocently, yet curiously, Apu pushes his own cause by embarrassing his mother by saying: “Oh mother! Don’t you have any money?!” We see an appetite for knowledge over and above uttering chants and worshipping. We witness the enactment of achievement over ascription. In Apu, we see a defiance of the supposed. He denies what he is disinterested in doing. While his mother and his grandfather and the societal expectations try to pull him towards the family profession (jajmani), while the circumstances compel him to remain a priest—he goes against all odds to exercise free-will and agency.

His quest and journey are quintessentially modern. It is a journey from the village to the city. It is a journey from poverty to aspiration. From having no ambition to nurturing a modern ambition. From abandoning the inherited profession and exercising freewill—to get educated; to move towards the city; to study further; to choose a profession of his choice. And at the heart of his journey, lies the quest for education (vidya). And this vidya is very different from the scriptural knowledge that Apu’s father possessed. It is a narrative of conflict between puja (tradition) vs education (modern). Apu chooses the latter and overcomes traditional authority.

The Unknown World comes to Apu in form of Print

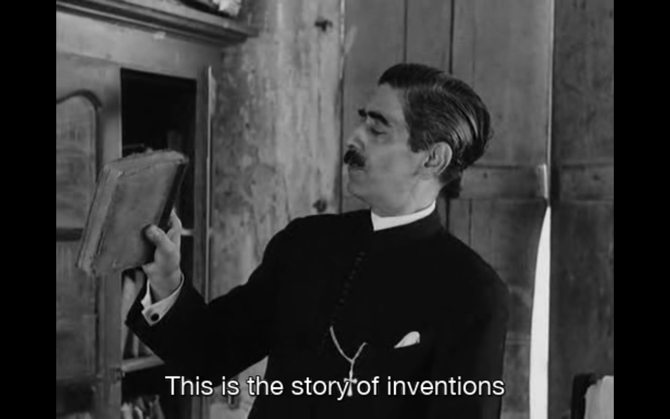

<p style="text-align: justify;">After Apu manages to impress the school-inspector by his diction and reading skills, the principal calls him over for a praise. He promises to help him out in every possible manner to support his progress. He offers him books from his personal collection. Books of modern science that stands for rationalism, modern travel that stands for modern exploration, and modern biographies of great-men that stands for modern practices of documenting and archiving lives of modern heroes. The headmaster says that one has to read these books to expand one’s horizon beyond the text books. He categorically lends Apu books on distant North Pole and Eskimos, Livingstone’s Africa expeditions, stories of modern invention, and biographies of scientists. Through modern printed text, the distant and unseen and unknown world comes to Apu in one remote corner of Bengal. Apu is burdened by the new load of knowledge—the baggage of books that will expose him to the world and eventually dislocate him from his traditional locale. </p>

The Ambition of the Unvanquished over Traditional Authority

In school-final examination, Apu comes second in the district and returns home with a globe in his hand. The globe is a definitive symbol of his prospective outward journey, and his attraction towards the world outside.

Excitedly, he declares about his wish to study further and go to the city for that purpose. Calcutta—the big city—becomes an aspired destination to satiate Apu’s larger goals.

The possessive mother is disheartened by the thought of her son going away from her. When Apu asserts himself, and his ambition to go to the city and study, Sarbajaya gets furious. First, she raises the issue of funding. Apu refutes it by stating that he will manage on his own and find some work in the city to raise funds. Sarbajaya refutes. What will happen to her, if Apu goes away. How will she manage on her own—all by herself; who will take care of her living and finances, if he stops serving as a priest in the village? To which Apu firmly replies: “If I don’t study, then will I be a priest all my life?” Sarbajaya firmly asserts her traditional authority to say: “What’s wrong with that? What’s wrong with the son of priest becoming a priest”, and asks her son to shut up. At this point, Apu goes a step further by screaming at his mother: “Will it always be the way you decide?” The mother replies back saying: “Yes, that’s how it’ll be”. And Apu screams louder by saying “NO”. At this point Apu is slapped by Sarbajaya. Even though, in the next morning, eventually she agrees to let go of Apu.

We realize that Apu wants to be in charge of his life-trajectory. Her mother cannot make decisions for her; not any longer. Or, to put it differently, he will not allow his mother or motherly expectations to cancel out his career options. That choice-making and its trajectory—both are fundamentally modern.

Apu and/in the Modern City

Apu arrives in colonial Calcutta as a representative of rural-urban migration in early twentieth century in a train that nudges into the urban landscape.

Apu is awestruck. In the establishing-shots that places Apu amidst the metropolis—we find him puzzled by the moving traffic and imposing building. He is liberally and metaphorically at crossroads with a suitcase, bedding and globe in his hands. With his belongings, he appears out-of-place. Though very soon that equation will alter, and he will make the city, his own, in no time.

He finds shelter in the metropolis using the reference of the village head-master in a printing press, where he is offered a night-shift-job in lieu of his free-stay.

In his room, Apu is fascinated to find the presence of an electric bulb that was unthinkable in the village.

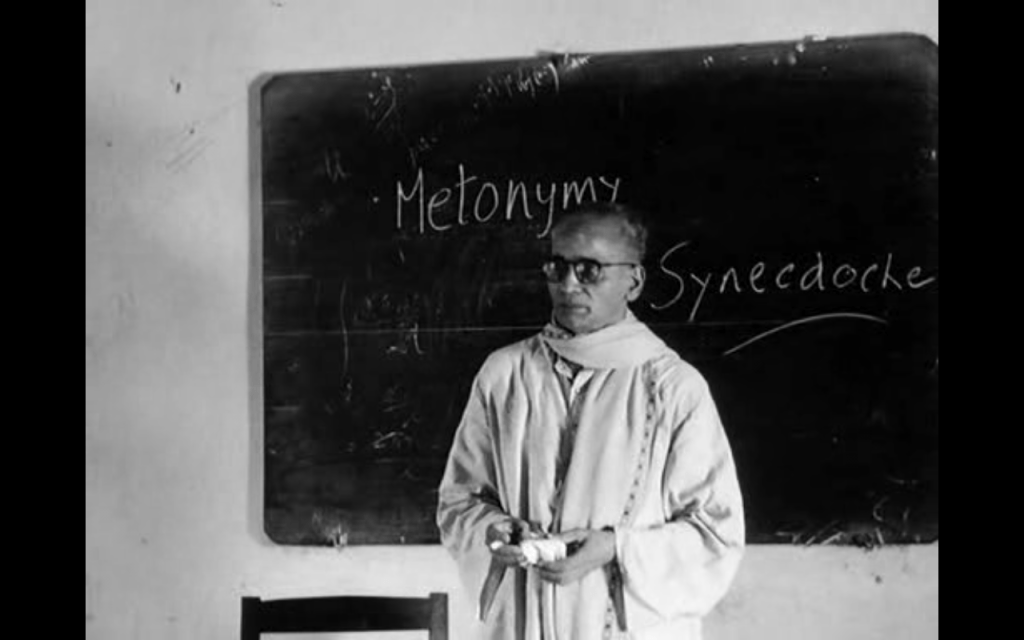

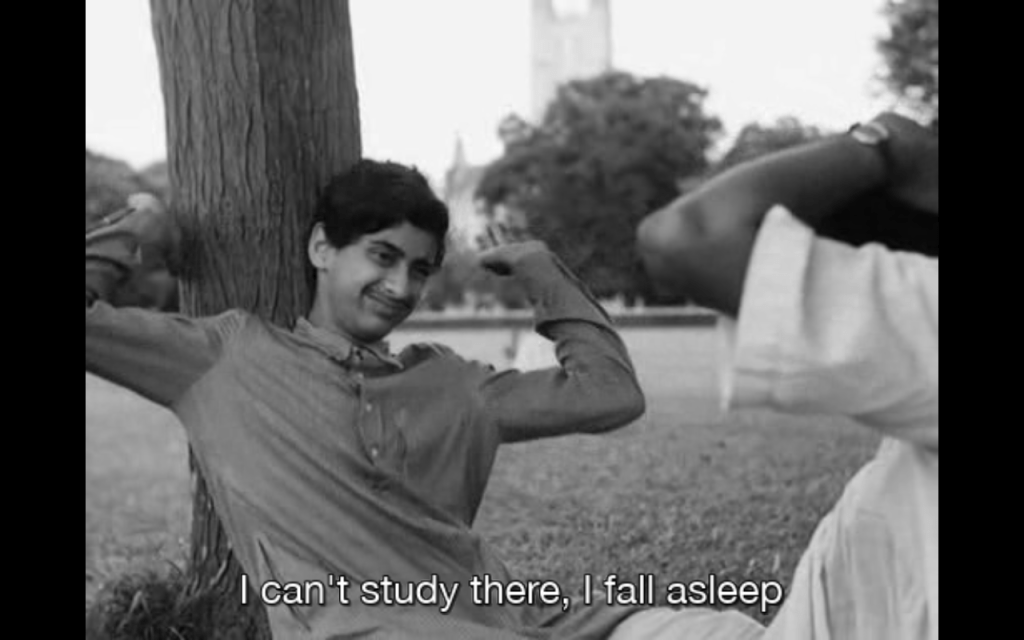

Apu’s struggle for existence is not an easy one, as he has to work after college for long hours in the press to sustain himself. He is seen dozing off in the class while the English professor is explaining ‘synecdoche’—a figure of speech based on association. Apu’s association with the new found urban spaces is a narrative of on-going absorption and adaptation.

We enter an industrial-riverine urban-scape, after Apu and his classmate is thrown out of class for being inattentive. As Apu is provoked to bunk classes. In a scene that starts with industrial fumes and smokes arising out of steamers on the Ganges, Apu acknowledges his ambitious self, quite blatantly.

When his classmate question Apu: “Don’t you want to go abroad? Don’t you have any ambition? Will you remain like a frog in the well?” Apu is quick to reply back by saying, “If I had no ambition I would have stayed back in the village, and continued to be a priest.”

The Growing Distance between the Mother and the Son—Difference of World Views

Sarbajaya’s wait for her son—Apu—is quite enduring. While she longs and wants more of him, Apu grows increasingly distant. In the distant horizon, we see the train that runs through the Apu-trilogy. In Pather Pachali, the train is an enigma for the village kids, as they discover its rattling presence—piercing through the rural landscape. Train is a source of wonder. The sight and the sound of it is found to be baffling. With its pace and gravity, it impresses the childish curiosity of Apu and his elder sister. In Aparajito, the train is the conjoiner between the village and the city. While for Apu, it is the facilitator of mobility and aspiration. For his mother, it signals the possibility of Apu’s increasingly-rare and much-awaited return from the city. Apur Sansar sheds the railway-romanticism to expose the killing-capacity of the tracks amidst dense urban-settlements for the poor.

When Apu returns to the village, and converses with Sarbajaya, we realize the impact, the modern city and the modern education has had on him. He is disinterested to attend to Sarbajay’s curiosities around his urban experiences. In fact, he dozes off in the middle of a conversation, while his mother reveals her parental insecurity that emerges out of aging and isolation.

The harsh reality is: Apu becomes indifferent to his mother and disinterested in rural life and rural folks. He walks away with disdain from a village show. Village holds no significance in the new-found track that he has embarked upon and embraced.

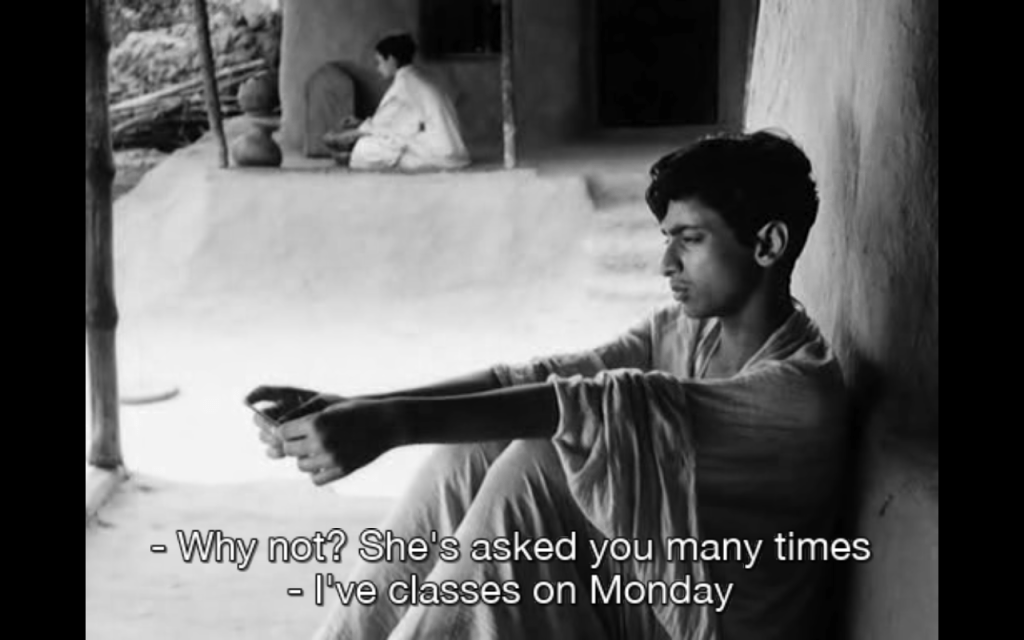

It is not just a case of physical detachment between the mother and the son (as we see in this frame), but also a case of growing emotional detachment and intellectual incompatibility between them. He refuses to visit a relative in the village despite his mother’s repeated insistence. He is rather very eager to return to the city as soon as possible. City is luring and definitely more relatable. Village has turned boring for him. Apu leaves.

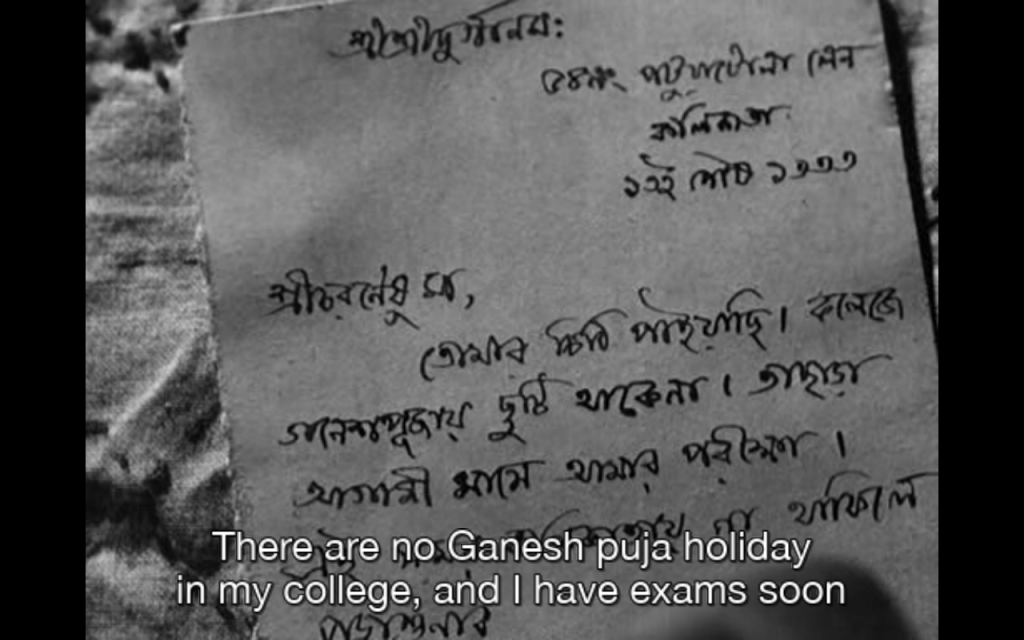

Later when Sarbajaya writes to Apu to pay a quick visit, he refuses to return, citing the excuse of upcoming exams.

But Apu does not go Home. Instead, he cultivates an excuse to avoid. The mother stops demanding any further even though she does not stop expecting her son to turn up without notice. The sound and the sight of the moving train reminds her the possibility of Apu’s possible home-coming.

For Apu, the idea of habitat has changed permanently, as he has grown out of the village. Village has become boring, unexciting and sleep-inducing for Apu, as he rightly acknowledges.

Apu is on a different trajectory of his own that has a different purpose and meaning, and which is far removed from the rhythm of the rural. For he has entered the world of wonder that the city and the science laboratories offer.

The Rise of the Individual—The Demise of the Primordial

Sarbajaya suffers mentally and physically and dies soon in Apu’s absence. In Pather Panchali, the mother-character was established as protective, care-giving and concerned. The purpose of her life has centered around children-welfare. Therefore, it was not easy for her to let go and part ways with her son—the only surviving close-kin that she is left with after the demise of her husband and daughter. The mother-figure soon recedes to oblivion.

Instead of taking recourse to overt exposition of sentimentality, Ray makes the mother-character determined, and not begging for attention. In her recluse, Sarbajaya does not stop expecting Apu’s return, but she draws a line. Her (in)actions are consequences of a restrained abhiman, which could have been healed only by Apu’s timely arrival at regular intervals or by his constant attention. Sarbajaya is denied of son’s affection. She wishes his return and mourns his absence silently, and suffers the pain of a cruel detachment. However, self-respecting Sarbajaya does not want to be the principal distractor in Apu’s life. After realizing and coming to terms with the abandonment, she surrenders. In her non-assertion, we find a cinematic trajectory dipped in high-realism—devoid of melodrama—way ahead of its times.

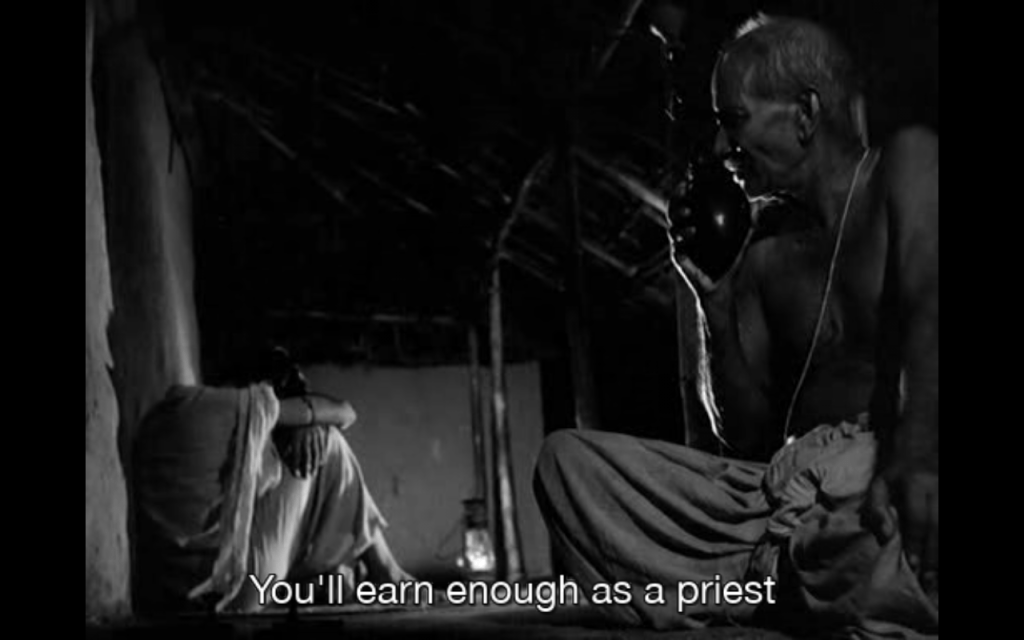

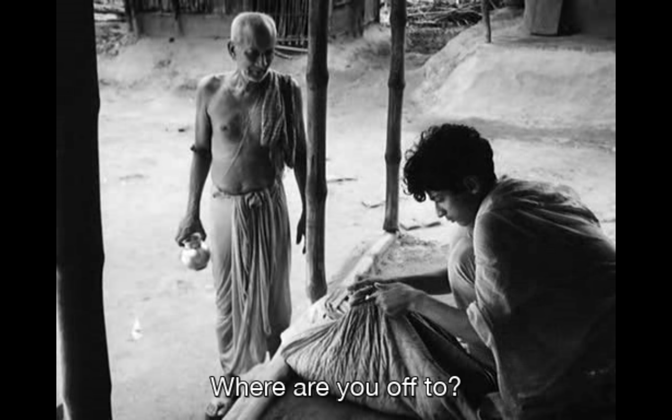

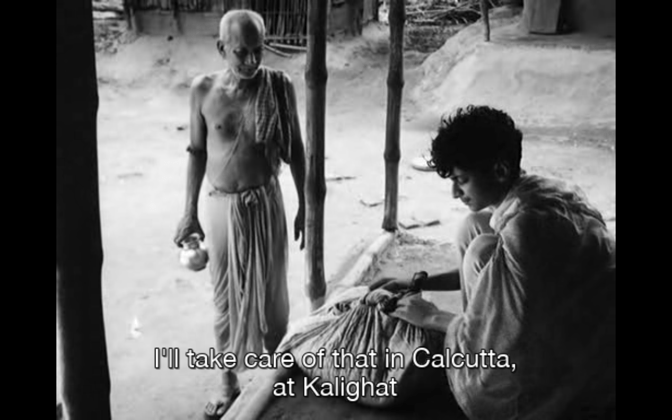

Upon his return Apu gets to know about his mother’s demise. His cries and repents are short-lived. His grandfather makes a final effort to hold Apu back in the village. He asks Apu to do the last rituals and stay-back in the village and embrace priesthood for a living.

In the next shot, in the next morning, Apu is seen to pack-up and leave. On being asked about his sudden departure, he says he has to attend college and give examination.

His departure, we know is final. There is no point of return. And there is no point in returning, as well. He chooses to relieve himself from the clutches of primordial ties, pre-determined occupation and familial grip to choose and chase his ambitions that are entirely his own. And that choice is quintessentially modern—as is the symbolism of a bare-feet Apu, when he departs for the city, and returning in shoes, every time comes from the city.

Like the swinging of the stations-pendulum, when Apu was once indecisive about his exodus to the city to prolong his village-stay to satisfy his mother—his final plight to embrace modernity—has no iota of ambiguity. He remains undefeated, unvanquished, unstoppable.

Apu is unconventional. In comparison to the long history of the typical servitude of the son towards his mother in Indian cinema, Apu is a huge aberration. Instead of blind devotion, he chooses the path of self-development over familial obligations. He leaves the family behind, as you have to leave a lot behind for the quest of modernity. What may seem to be an apparently selfish act—is abjectly modern. Modernity demands dissociation with primal roots to accommodate a transition that is not just spatial, but is also individualistic and ambitious. Apu—undefeated—becomes the template of post-colonial modernity; even though it happens to be a harsh reality of pragmatic departure to chase ambition. Apu’s alienation from his traditional roots is complete and Apu is set free for the modern world.

Apu is the young nation who embodies the idea of choice and freewill in a free country. Modernity offers choice to defy the ascribed obligations. Apu embraces the promise of modernity that provides options of education, livelihood, city-life, and new companionship. In that progressive package, any force that holds one back, is an obstacle. A care-giving sacrificial mother can be sacrificed too, if needed. The harsh reality of this abandonment, is in conflict with the representation of the mother-figure as a celebratory figure of benevolence in popular cinema. The demise of the mother turns the moral compass in a different direction altogether in the world-of-Ray.