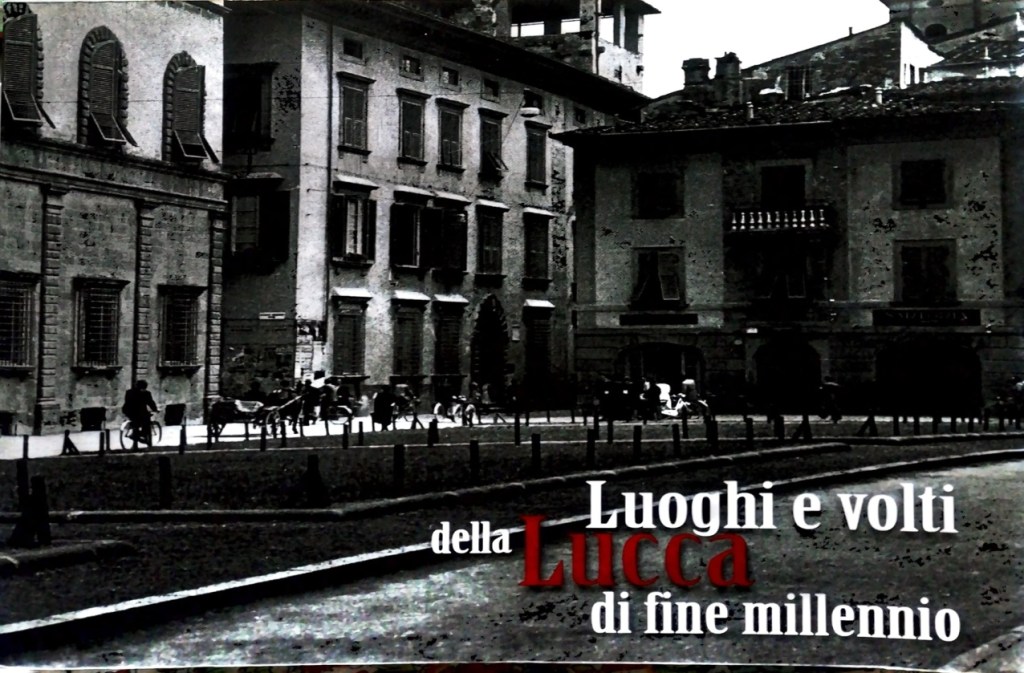

After lunch the conversation shifts to the old farmers’ market in Piazza Anfiteatro. It was a beautiful, busy market, Giuliana remarks as we drink our coffee in fond recollection of one of those lively extinguished local scenes now replaced by supermarkets. While she recounts her childhood memories of her home town, Roberto takes a photo book to show me: a collection of black and white photographs of the historic city of Lucca entitled, Luoghi e volti della Lucca di fine millennio, published in 2011 by Pacini Fazzi.

Lucca, the tiny walled-city where we all live, lies in Central Tuscany near the Tyrrhenian Sea, on the Serchio River, a close neighbour to its historic rival city Pisa and some 70km from Florence.

When I hold the book in my hands and recognise the image of Piazza San Bernardini on the book cover, I am suddenly gripped by nostalgia—an itinerant nostalgia that crosses borders and epochs, as though I am visiting a lost memory, mourning for a vanished world. And when I turn to the first pages of the book which show the aerial photographs of the city I feel as though I’m leaving again and returning to a place that is both deeply familiar and completely foreign. The photographs become both a transit space and a place of arrival. Nostalgia is distance and familiarity simultaneously always both at once, with a particular ache that binds them. The Spanish poet Antonio Machado:

Where does this road go?

I go travelling, singing,

into the road’s far distance.

Why do black and white, particularly the early Italian photography, evokes an intense form of nostalgia that is absent in coloured photography? Why is looking at old images of a place, of a barely remembered past in black and white so compelling, almost heartbreaking that one can only approach them in longing?

The history of Italian photography in the first half of 20th century is exhaustive, its photographic resource is prodigious that any Italian who is curious to get a detailed glimpse of his city’s past has generous recourse to local photographic archives. The beginnings of photography in this country was exploited first and foremost as a device for documenting Italian society. Luoghi e volti consists of images of the city of Lucca in the beginning of the 20th century with the earliest images dating back from 1898 and the latest taken in 1980 almost a hundred years apart. The series of black and white photographs are fascinating in their documentation of the city’s architectural wonders and also of the city’s public life: a walk in Via Fillungo or on the walls, the bustling farmers’ markets in the piazzas, religious ceremonies like the procession of Santa Croce and the feast of Santa Zita, secular events like sports and music concerts and carnivals, etc,–collective moments which to this day articulate the life of the city of Lucca.

More fascinating even are the images that offer a poignant look into a way of life that struggled to survive the modernisation of Italy since the 1950s into a first-world consumer society. The world of small scale artisanship, of guilds, of peasantry—a world that is becoming more and more archaic, extinct, as the onslaught of technology reconfigures society and the nature of work. An Italy that is barely visible in the actual world but in the silence of black and white photographs. The pictures of terracotta and figurine makers, the textile weavers, the tobacco factory workers, and peasants are the most haunting images in the book. Their melancholy is profound because they look so remote; they are the most nostalgic because their absence implied the disappearance of a certain way of life, of a culture that can only be heard in old men’s stories; and beneath their silence is a gasp, a sob, a whimper.

To look at these images is to witness how a place submits to the wreckage of time. Though for the most part the city of Lucca has courageously preserved its architectural identity it nevertheless has succumbed some aspects to the imperatives of modernity. Behind the structural and architectural changes that occurred from the beginning of the 20th century to this day is the unpronounced alterations in social reality, in our ways of living and inhabiting a place. Observe the earliest photographs of Corso Garibaldi taken in 1900 vis-à-vis those taken in 1925-1930 and 1945-1950 respectively show the evolution of a certain area of the city. Corso Garibaldi in 1900 was wide, unimposing, somewhat too open, hospitable to frequent indeterminate meetings and casual interactions that allow for a freer movement. Observe now how Corso Garibaldi became narrow through the years which suggests that the way of life has become more hectic, busier, utilitarian, the movement minimal, no longer people-oriented but car-oriented. As visual records these photographs are a summary of losses, of traditions maimed by innovations, of integration elbowed out by exclusion, of the new inevitably winning against the old.

The photographs of farmers’ markets testify to the vanishing old ways. A photo of a farmers’ market in Piazza Anfiteatro taken in 1955. Men and women and boxes of fruits and vegetables crowd the square. The farmers indistinguishable from the clients themselves. The angle of the photograph suggests that it was taken from the window of a second floor building looking down on the square. One can guess that it is early Sunday morning because of the way people look, their posture relaxed; men’s hands are inside their side pockets, women carry their bags eagerly, taking their time as they gossip by the side of large boxes. One can hear from the silence of the image the bustle, the voices simultaneously talking, laughing, lamenting, negotiating. It is an accurate picture of a communal sense of belonging, where people know their place, where everybody is dependent on everybody, producers and clients in direct contact. Today, the once buoyant and busy farmers’ markets in open squares have largely been replaced by corporate supermarkets, and the implication of this modernisation on the community can be observed behind the photograph.

Once there were clients and now there are customers. Clients can be identified as acquaintances or friends of the producers or farmers themselves; an organic link binds them that makes business transaction almost always negotiable. To be able to negotiate is a social practice, a kind of collaboration that recognises the dependency of both parties; because essentially they belong to a single community which renders any hierarchy useless. Customers cannot be claimed as such; they are claimed to be “always right”; uncontested, served, distanced from the producers which have become faceless and remote, while small-scale producers themselves have mostly been wiped out in favour of large scale industrial agriculture emblematic of corporate supermarkets. In this economic order nothing is negotiable for the price is fixed by the invisible hand. Both producers and customers have become immobile, passive, rendering their organic relationship irrelevant. The producers obey, the customers choose between product A and product B which give the illusion of choice. The customers stripped of their agency and their ability to negotiate are reduced to being consumers, alienated from the world of production, subservient to the dictates of the market, atomised by their buying power whose only value lies in its relation with the articles of consumption. The disappearing tradition of open-air markets deprives the future generations of the significance of collective gathering, of direct interaction with small merchants and producers, of the social practice of negotiating which creates intimacy between clients and producers, all of which affirms and confirms the communal sense of belonging.

The more I look at these images the more it feels like I’m reading a love letter from a stranger of a long time ago whose memories have long been buried in my mind suddenly arise after a lapse of years with intensity and longing. I remember the lines from a particular poem by the great Russian poet Marina Tsevetaeva:

No one has ever stared more

tenderly or more fixedly after you…

I kiss you—across hundreds of

separating years.

But why nostalgia for a place whose geography I do not belong to, whose history is alien to me, whose people are not my people?

There is an aesthetic quality in early Italian black and white photography that reconfigures the experience of looking, as though to look is to retrieve the remains of early memories of loss: a migrant nostalgia. That makes black and white not as welcoming as coloured photography; for coloured strives to be permanently in the here and now; its aesthetic is the random, the simplistic and often times the superficial, thus it incessantly repeats itself which eventually renders the image meaningless. One cannot approach the black and white (particularly the most compelling images) in a haphazard, unpremeditated, random encounter; it aims to be of rarity, thus it can only speak in the language of the far away. These images bid a stillness that is close to a kind of mourning as though we are approaching that which we have already lost. The American poet Charles Wright echoes this sentiment in the poem Cicada: We measure what isn’t there. / We measure the silence, / we measure the emptiness.

To some extent these images approach the status of paintings because of the haunting stillness they carry within them. But there is a qualitative difference between the stillness of paintings and that of black and white photography. The stillness of paintings is continuous, always present, or rather timeless by virtue of the fact that one can trace the brushstrokes of the painter that make the work of art more immediately present. That of the black and white is a kind of negation; time has stopped, everything is abandoned, life has past moved on and is continuously moving on; it is the stillness of the left behind.

What is revealing today in looking at these images is that they witness us and not the other way around. Like the passengers in the photographs of city trams, trolley busses, and horse carriages—they stare at the lens of the camera with baffled eyes carrying with them their desires, their histories, their world as they detour across our memory.

These photographs do not simply offer us a record of what the place was or what the people were like back then but rather the glimpse of the images is turned on us—we are being witnessed by the nostalgia that accompanies us in our seeing—seeing what the world has become around us and what we have become in consequence, and in that becoming the immense and immeasurable loss that we did not witness comes to us through a particular mourning of memory.

Looking at these photographs we are already in mourning not so much as a grievance for a lost memory or a forgotten life—no amount of photographs can recapture the vanished past. We are in mourning because the images claim our memories intensely by excluding us, telling us we are no longer part of what once was, a world has died and abandoned us, and as we awake from forgetfulness, oblivion, and indifference we ourselves are turning into memories.

There is a picture of an overloaded horse carriage outside Porta San Pietro along Viale San Concordio on a rainy day in 1948, three years after the war. Barely visible is the image of a man walking in front of his carriage alongside the horse, holding an umbrella, all his belongings, all that is dear to him is behind him on the carriage. Looking at this particular photograph we experience the real texture of time. Time compels us to move on, further on; for the moment will arrive when you must part from a certain place forever and there is no turning back. Listen to the voice of the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish:

… we can see ourselves turning into memories. We are these memories. As of this moment, we’ll remember each other as we’ll remember a distant world disappearing into a blueness more blue than it used to be. We’ll part in the pitch of longing.